Why do career centers need digital-first advising practices instead of simple virtual appointments?

Digital-first advising requires intentional session design, collaborative workflows, and engagement monitoring to address disengagement, misinterpretation, and passive participation common in virtual environments.

Most career centers treat virtual advising as a simple channel swap - moving in-person appointments to a video call.

However, this approach fails to address the unique failure modes of digital interaction, like disengagement, misinterpretation of non-verbal cues, and the inability to co-create artifacts effectively. A

According to a 2025 EDUCAUSE report, while 85% of institutions offer virtual advising, less than 20% have formal protocols for reading digital body language or verifying student focus, leading to inconsistent and often ineffective sessions.

The core issue is a failure to re-architect the advising experience for the medium. A

true digital-first model requires new structures, tools, and assessment methods designed specifically for the virtual environment.

This shift from channel substitution to intentional redesign is critical for delivering scalable, high-impact guidance.

How do you structure a virtual session for maximum engagement?

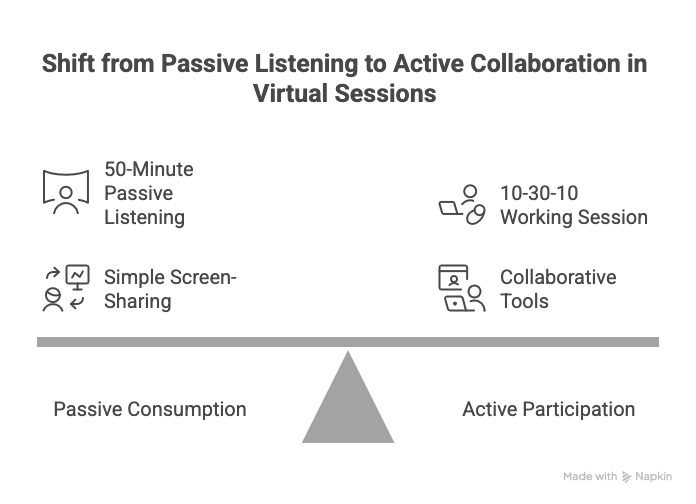

A virtual session must be structured around co-working and artifact creation, not passive conversation. The ideal "50-minute" session should follow a 10-30-10 format: 10 minutes for rapport and goal setting, 30 minutes for active, collaborative work on a specific artifact (e.g., editing a resume in a shared document), and 10 minutes for summarizing actionable next steps and setting a follow-up.

This "working session" model combats the primary failure mode of virtual advising: passive consumption.

A 2024 study from Stanford University on video conferencing fatigue found that sustained, passive listening leads to cognitive overload and diminished focus.

By shifting to a collaborative "do-with" model instead of a "tell-to" model, advisors ensure the student is an active participant.

For example, Arizona State University's career services encourages students to have documents ready for live editing, making sessions inherently interactive.

Verification of this model's success is simple: Did the session produce a measurably improved artifact (e.g., a resume with a higher rubric score) and a documented action plan?

Also Read: What are the best practices to set up virtual career treks?

What tools are essential for effective screen-sharing and document review?

Effective virtual review requires tools that enable simultaneous, multi-user collaboration and annotation, moving beyond simple screen-sharing. Platforms like Google Docs or Microsoft 365 for live co-editing, Figma or Miro for visual brainstorming and portfolio reviews, and tools with persistent annotation features are essential. Standard screen-sharing often turns students into passive observers; collaborative tools make them active partners in the review process.

The goal is to replicate and enhance the "side-by-side" experience of an in-person meeting.

When an advisor simply shares their screen and points with a cursor, the student is watching, not doing.

When both advisor and student are in a Google Doc, making edits and leaving comments in real-time, the cognitive load is shared, and learning is active.

Wake Forest University provides students with templates in Google Docs to facilitate this exact type of collaborative review during virtual appointments.

The effectiveness can be verified by reviewing the document's version history, which serves as a direct artifact of the collaborative work performed.

Also Read: How to boost student engagement in career treks?

How can advisors accurately interpret digital "body language"?

Advisors must shift from interpreting holistic body language to tracking specific micro-behaviors indicative of engagement or distraction. Key signals include eye-gaze (are they looking at the screen or elsewhere?), typing patterns (are they taking notes or messaging?), tab-switching (indicated by subtle screen glow changes), and response latency. These cues are more reliable indicators of focus than trying to interpret posture or facial expressions on a low-fidelity video feed.

Traditional body language cues are often lost or distorted through video. Therefore, advisors must be trained to look for digital signals.

For instance, asking a student to summarize the last point can be a direct probe to check for comprehension and focus.

Verification involves self-reporting and direct behavioral checks. An advisor can implement a "three-minute check-in" where they pause and ask, "What's your key takeaway from what we just discussed?" to gauge active listening.

Also Read: Hiration vs. Vmock - which is the best option for your career center?

What techniques keep students focused and prevent multitasking?

To maintain focus, advisors must use structured interaction techniques that require active student input at regular intervals. This includes "calling out" the student by name to ask targeted questions, implementing a "shared screen" policy where the student drives the navigation, and using interactive tools like polls or a virtual whiteboard to break up passive listening. These methods create an environment where multitasking is difficult and disengagement is immediately apparent.

The default state for many students in a virtual call is passive listening, which invites distraction.

Research from the University of California, Irvine highlights that it can take over 20 minutes to refocus after being distracted. The key is to prevent the distraction from occurring.

By making the student the "driver" of the screen-share, they are forced to be actively involved.

An example from the University of Central Florida's virtual advising guide is to have students share their LinkedIn profile and make edits themselves as the advisor provides verbal guidance.

This interactive approach can be verified by observing the student's ability to execute tasks and respond to prompts in real-time.

Also Read: 5 Best Practices to Help Students Build Job-Winning Portfolios

How should career centers troubleshoot common remote advising issues?

Career centers must develop a standardized, multi-step troubleshooting protocol that advisors can deploy without escalating to IT. This protocol should start with the simplest solutions (e.g., "turn video off to improve bandwidth"), move to intermediate steps (e.g., "switch to a phone call for audio while using screen-share"), and end with a clear rescheduling procedure if technical issues are insurmountable. This creates a consistent, professional response to inevitable technical failures.

Without a clear protocol, advisors may offer conflicting or unhelpful advice. A standardized approach ensures a baseline quality of service.

For example, a common protocol could be:

- Advise a browser refresh

- Suggest disabling video

- Switch to a separate audio channel (phone call)

- If unresolved in 5 minutes, immediately reschedule and send a follow-up with links to institutional IT support.

This protocol’s effectiveness can be verified by tracking the number of sessions successfully completed versus those requiring rescheduling after a technical issue arises.

Also Read: 5 Tips to Build Employer Partnerships for College Career Treks

Framework for Assessing Digital Advising Modalities

| Modality | Key Student Behavior | Advisor Action | How to Verify Effectiveness | Common Failure Mode |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Synchronous Video | Active participation and co-creation | Structure session around a shared artifact (e.g., Google Doc) | Review version history of the document; student can articulate next steps | Student becomes a passive viewer; advisor does all the work |

| Asynchronous Video | Reviewing and applying feedback | Provide screen-recorded feedback with clear, timestamped comments | Student submits a revised document reflecting specific feedback points | Feedback is too generic; student ignores the recording |

| Live Chat / SMS | Asking specific, transactional questions | Use pre-written templates for common queries; escalate complex issues | Resolution time under 5 minutes; low escalation rate for simple questions | Advisor gets pulled into a long, inefficient back-and-forth conversation |

| Group Webinar | Engaging with content and peers | Use interactive polls, Q&A, and breakout rooms | High participation rates in interactive elements; positive survey feedback | Session is a passive lecture with no student interaction |

Wrapping Up

An intentional digital-first advising model depends on intentional system design.

Session structure, collaborative artifacts, digital engagement signals, and follow-up workflows only create impact when they operate as a connected whole.

When these elements live in isolation, advisors lose context and students experience advising as a series of disconnected moments.

An integrated ecosystem changes that dynamic. Connected data across resumes, interviews, advising notes, and student actions enables continuity, accountability, and measurable progress over time.

Hiration provides the infrastructure to support this model, unifying career readiness tools with human-in-the-loop AI so advising moves from transactional support to an evidence-backed, scalable student journey.

When the system is designed for the medium, both advisors and students can stay focused on the work that matters.

Digital-First Advising — FAQs

How should a virtual advising session be structured for engagement?

Virtual sessions should follow a structured working model that prioritizes collaborative artifact creation, clear goal setting, and documented next steps rather than passive conversation.

Why is co-working on shared documents essential in virtual advising?

Shared documents transform students from passive observers into active participants and create measurable artifacts that demonstrate learning and progress.

What signals indicate student engagement in a virtual session?

Engagement is better measured through digital behaviors such as response latency, screen interaction, task execution, and verbal summarization rather than traditional body language cues.

How can advisors prevent multitasking during virtual appointments?

Advisors should require frequent student input, assign screen control to the student, and use interactive tools that make disengagement immediately visible.

What tools are most effective for virtual document review?

Tools that support real-time co-editing, annotation, and version history enable deeper learning and replicate the side-by-side experience of in-person advising.

How should career centers handle technical issues during remote advising?

Centers should deploy a standardized troubleshooting protocol that prioritizes quick resolution, alternative communication methods, and consistent rescheduling procedures.